Blog

Memory in Antagonistic Politics: Minutes from an “Antifascist September” in Greece

Emilia Salvanou:

On Wednesday 7 October, the Supreme Court of Greece passed its long-awaited verdict on the Golden Dawn party, declaring it to be a criminal organization. It was also held responsible for a series of violent attacks on immigrants and on its political opponents. This judicial milestone was in marked contrast to the relative impunity with which the Golden Dawn had operated until now. Its entrance into Parliament in 2012 had given it a certain aura of respectability with the mainstream media and members of the organization downplaying its fascist tendencies and presenting it instead as a new anti-system party that had arisen out of a unique combination of nationalism, anticommunism, and Euroscepticism. This tolerance of Golden Dawn violence ended in September 2013, however, when rapper, and well-known anti-fascist activist Pavlos Fyssas was fatally stabbed in an Athens café by members of the movement. His death sparked such an outcry that the police and public prosecutors were forced into action. Prominent members of the Golden Dawn, including its leader, were arrested and the party gradually collapsed; it lost all its seats in the 2019 election.

From 2015 Golden Dawn rally in Athens, with visible neo-Nazi symbols. Photo by DTRocks.

The start of the trial was delayed for almost two years and has been going on for almost five and a half. In the interval, Fyssas and other victims were not forgotten. Indeed, keeping their memory alive and in the public mind became a focus of antifascist activism and entailed a wide range of initiatives around the country: from antifascist protests to public discussions, concerts, interventions at schools and neighbourhoods, athletic tournaments and screenings of documentaries in the period around the anniversary of Fyssas’s death.

With time, the events recalled in the “Antifascist September” movement also broadened. In 2018, LGBTQ activist Zak Kostopoulos was viciously kicked to death in the centre of Athens in broad daylight. The apparent impunity with which such homophobic violence could occur provoked new outrage. As a result, LGBTQ and feminist activists joined forces with the antifascists, forming the “Anti-fascist/Anti-patriarchic September” in 2020. This merger was based on the argument that both murders, as well as similar incidents of violence taking place around the country in recent years, have a common origin: the diffusion of a far-right ideology and corresponding practices in Greek society in the 21st century, especially since 2010. Even though Golden Dawn was not re-elected in 2019, the organisers of ‘Anti-fascist/Anti-patriarchic September’ believe that their ideology continues to inform many cultural practices in Greek society. Centrally, in exclusionary practices directed against whichever group is perceived as a ‘moral danger’ – of which refugees are the most recent, but not the only, example – as well as in the disciplinary discourse which discourages critical thinking as nationally harmful.

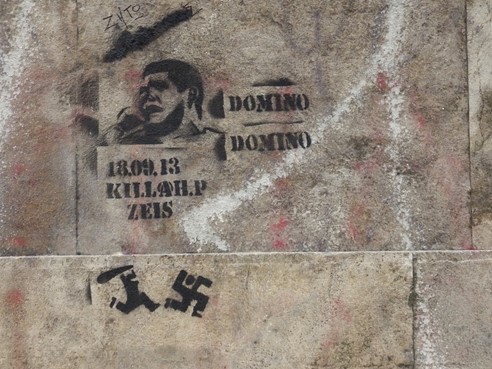

Stencil dedicated to the memory of Pavlos Fyssas (Killah P.) with the date of his death and the word ZEI, ‘he lives’. (ZEI carries a strong memory load in the Greek cultural context, linking back to the assassination of Grigoris Lambrakis in 1963 and the youth movement sparked in response.) Photo by aestheticsofcrisis.

“Antifascist September” is not the first time that assassinations have sparked a social movement in Greece. Nor is it the first time that such movements have made use of memory to place themselves in a genealogy of struggle for the improvement of society. The dichotomy between democracy and reactionary conservatism has a long history in post-war Greece, which reached a climax in the 1960s and had a short-lived revival in the late 2000s. The assassination of politician Grigoris Lambrakis, a member of the Resistance in World War 2, by the deep state in 1963 and the murder of student Alexandros Grigoropoulos by a police officer in 2008 sparked similar youth-quakes and became crucial sites of memory for the political left-wing. The recent commemorations of Fyssas and Kostopoulos activate the memory of previous ones. The connection was made explicit, for example, in the open discussion titled “Lambrakis-Fyssas: Fascist Assassinations, Then and Now”, which was organized in framework of the 4th antifascist festival in 2016, or in this rap song in memory of Lambrakis and Fyassas.

Thousands of people were on the streets of Athens to welcome the verdict of the Supreme Court on 7 October. The categorization of the Golden Dawn as a criminal organization has been welcomed with cries of “Nazis belong in prison.” These echo the many profile icons on Greek Facebook that, as part of “Antifascist September,” have been decorated in the last weeks with a banner depicting a blood stain and a caption reading “They are not innocent. Nazis to prison.” The reference to Nazis was not coincidental, of course, since members of the Golden Dawn had cultivated the association with historic fascism through their swastika-like logo and their penchant for torch-light processions. But the deliberate framing of the Golden Dawn as Nazis by their opponents was also a way of evoking the deep memory of the ant-fascist struggle in Greece from the 1940s through the dictatorship and into the present. The Supreme Court’s verdict (headlined as the “biggest trial of fascists since Nurenberg”) is seen by all parties as a milestone in a much longer struggle. In Greece, political controversy is played out in the field of social and political identities – identities that draw from the repertoire of the past. The supreme court’s decision is not only important for demarcating the limits of democracy. It will be an important power factor in the ongoing struggle of Greece’s two opposing cultural systems and their opposing memories.

‘Red Stuff Fassade – Pavlos Fyssas – never forget!!’. Photo by seven_resist.