Blog

The Cross-pollination of Memories between Black and LGBT+ Activism

Daniele Salerno:

In spring, thanks to wind and insects, pollen grains can be carried from one flower to another of a different variety. This is what botanists call cross-pollination, and it sustains natural diversity. As Lisa M. Corrigan argues in her work, cross-pollination also exists in culture: stories may travel over to other stories, moved by people and carried by cultural objects and media – books, periodicals, images, movies, slogans. New varieties of narrative, symbols and words emerge from these encounters.

This happens in particular when people perceive similarities between the historical experiences of different social groups, and use this to build a dialogue between them, allowing for the transfer of memories from one group to another (and vice versa). Cross-pollination represents a very powerful cultural dynamic for shaping intersectional and international struggles in the construction of activist alliances across social and political groups. As emphasised by Michael Rothberg in 2009 with the idea of “multidirectional memory”, social groups “come into being through their dialogical interactions with others”. This is what, in the last few decades, has happened between Black and LGBT+ activism.

The start of one of the most powerful examples of cross-pollination between these two heterogeneous movements began in the spring of 1970 when the French homosexual writer Jean Genet illegally entered the US to support the liberation from prison of Bobby Seale and Huey Newton, founders of the Black Panther Party.

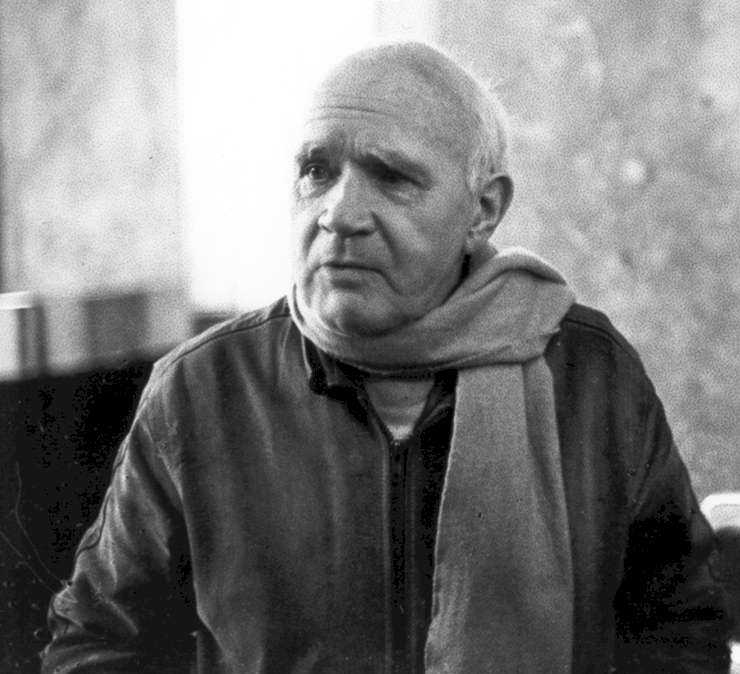

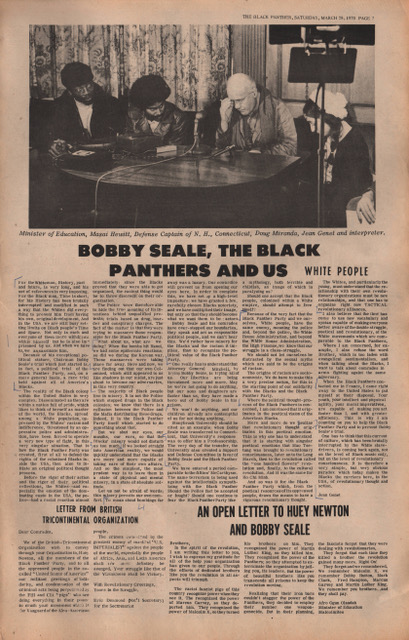

Genet was already a well-known writer, author of controversial masterpieces like Our Lady of the Flowers (1943), Querelle de Brest (1947) and The Thief’s Journal (1949). He toured the US in support of the Black Panthers and published two fundamental texts in the movement’s press outlet The Black Panther.

In “Bobby Seale, the Black Panthers and us white people”, Genet reshapes the anti-racist cause in terms of class struggle, presenting Black movements as “the carriers of revolutionary thought and actions”. In a second text, titled “I must begin with an explanation of my presence in the United States”, Genet describes the alliance between black and white people under a revolutionary cause, supporting a coalition between Black movements and the Left(s). He reshapes the case of Bobby Seale, by way of an analogy with Alfred Dreyfus and anti-Semitism in nineteenth-century Europe: “we are turning away from Bobby Seale because he is Black and in the same way that Dreyfus was guilty because he was a Jew […] there was a time in France when the guilty man was the Jew. Here, there was such a time, and there is still, when the guilty man is the Negro”. Genet identifies a common enemy – the police – and traces equivalences between the memories of different causes to build a coalition around the Black Panthers for the liberation of its two founders.

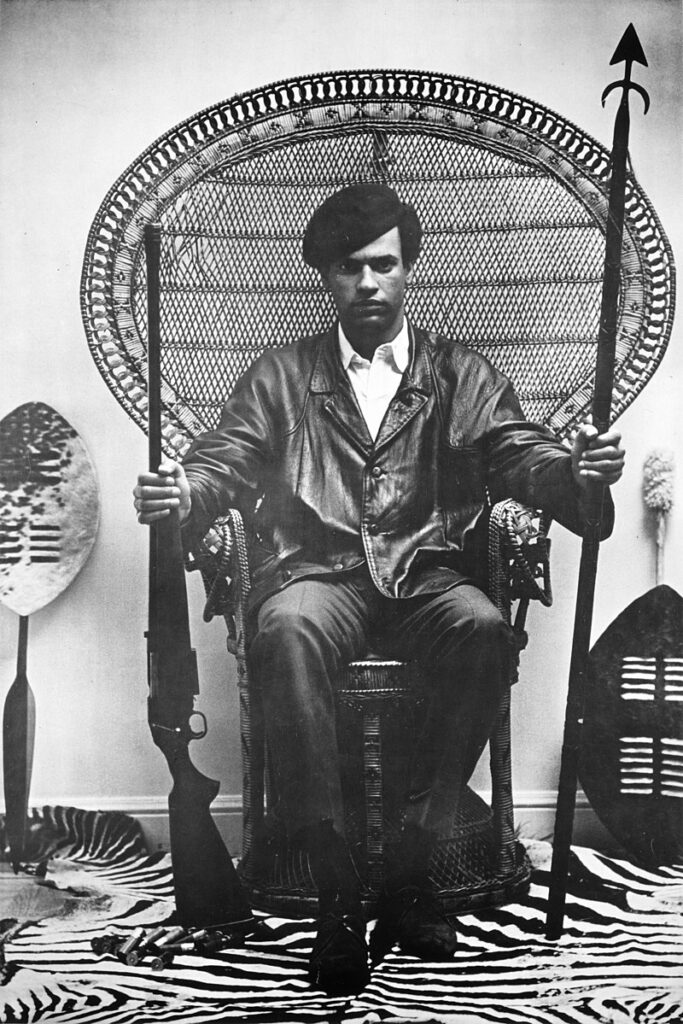

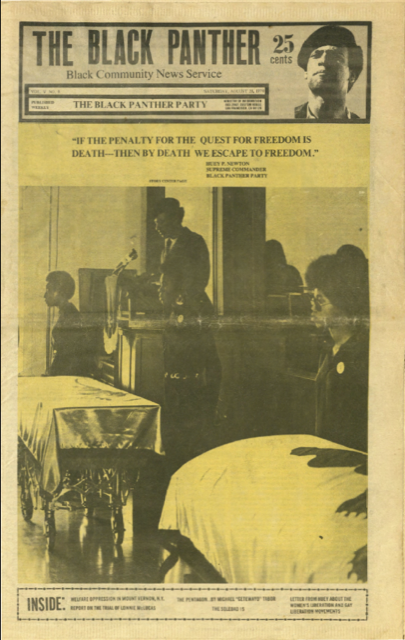

Genet went back to Europe in May 1970. From there, he continued his engagement in anti-colonial struggles and, in particular, joined the Palestinian cause (his experience in the US and in Palestine was collected in the posthumous book Prisoner of Love [1986]). However, his presence in the US had a lasting impact. Black Panther Huey Newton was released from prison in August 1970 and immediately after wrote a letter titled “Letter of Huey P. Newton, Black Panther Party Minister of Defence, to the revolutionary brothers and sisters on the homosexual liberation and woman liberation movements”, published in The Black Panther on 21 August.

Newton’s letter builds on the memory of Genet’s words and his rhetorical strategies: if Genet traced an equivalence between the memory of the battle against anti-Semitism and the memory of the battle against Black-oriented racism and the Black Panther’s cause, Newton traces an analogy between racism on the part of white people and homophobia and misogyny on the part of black people, pushing the chain of equivalences and similitudes that Genet had rhetorically started, in order to include the gay and women’s movements. Recalling how Genet had acknowledged the revolutionary struggle of Black people, Newton defines homosexuals as the most oppressed group and potentially “the most revolutionary” people.

Within a few months, Newton’s letter had been republished through the press outlets of many national gay movements. The US Gay Liberation Front published Newton’s letter in September in its periodical Come out!. As detailed research by Juan Queiroz and Germán Garrido has shown, this was thanks to the Third World Gay Revolution – a group of Black and Latinx homosexuals in the US who connected the homosexual struggle with anti-colonial political struggles and Third-Worldism. From the US the letter went global.

In September 1970, the letter was published in France in the first issue of the Maoist magazine Tout! on the initiative of Guy Hocquenghem, founder of the Front Homosexuel d’Action Révolutionnaire-FHAR. In a historical interview in Le Nouvel Observateur, credited as the first public coming out in France, Hocquenghem said: “I had wanted to share my first homosexual experiences following the publication of a text by Huey Newton in the first issue of Tout!”. In 1971, Luciano Massimo Consoli, a key figure in the Italian gay liberation movement, wrote a text for the first issue of FUORI!, the magazine of the Italian revolutionary homosexual front. Consoli describes Newton’s letter as a fundamental step in the struggle for the recognition and liberation of gay people. Consoli’s article was titled “To the revolutionary comrades”, an adaption of Newton’s title: “to the revolutionary brothers and sisters”.

The text was translated and republished many times and in different countries by activists militating in different organizations and for different causes. Newton’s letter was used by national homosexual movements as a sort of “letter of introduction” to leftist national movements in Europe and Latin America, supporting local alliances with Left and anti-racist campaigns.

The cross-pollination of memories offers a form of cultural and rhetorical support to coalitional and intersectional activism. The analogy between the oppression of gay, black and Jewish people made it possible to draw on the memory of historical injustices like colonialism and anti-Semitism in order to shape the memory of the oppression of homosexuals which was still to be written. This enabled the transfer and adaptation of symbolic and semiotic repertoires of protest, starting with the slogan “gay power”, which took the black activists’ “black power” as a model. If cross-pollination in nature allows for the growth of new varieties, cultural cross-pollination allows new slogans, words, and stories to grow, supporting alliances between social and political groups.